Eye

PORTRAITS AND SELF-PORTRAITS IN THE ”BOGDANOVIĆ” COLLECTION IN SREMSKA MITROVICA

Man and His Image

Since ancient Assyria and Egypt, this form of artistic expression passed through various stages, but it was always necessary to reach much further than mere external resemblance with the presented figure. Underlining the psychology of the painted or sculpted personality. Being aware that this might mean entering a mysterious field, full of magical features. This art genre has a long and rich tradition among Serbs as well. The collection of portraits in Nikola Bogdanović’s collection, one of the most important in Vojvodina, shows it in a unique way, through the prism of high modernism

By: Dejan Đorić

Reproductions: From the ”Bogdanović” Collection

Photo: Miloš Muškinja

Portrait is a word derived from the French expression for a picture of someone’s image, from Latin protahere = bringing to light. In art, it signifies the presentation of a certain human being, their face and figure. Besides purely external similarity, the psychology of the presented person should be emphasized in such form of expression. Thus, painters claim that their works penetrate deeply into the psychology of the painted person, which is not the case with photography. Modernism presented a thesis that a portrait doesn’t have to resemble the model, and that it should only be artistically good, which is unacceptable. Its

Portrait is a word derived from the French expression for a picture of someone’s image, from Latin protahere = bringing to light. In art, it signifies the presentation of a certain human being, their face and figure. Besides purely external similarity, the psychology of the presented person should be emphasized in such form of expression. Thus, painters claim that their works penetrate deeply into the psychology of the painted person, which is not the case with photography. Modernism presented a thesis that a portrait doesn’t have to resemble the model, and that it should only be artistically good, which is unacceptable. Its  purpose is to show a certain person or persons and preserve a memory of them. Judaism and Islam reject it, relating it with occult features.

purpose is to show a certain person or persons and preserve a memory of them. Judaism and Islam reject it, relating it with occult features.

Portraits can be classified based on the position of the head: profile, semi-profile (or three-quarters), profile perdu and full-face view; based on the position of the figure: presentation of the head or torso, which is half-length, and the entire figure. It can be in a lying, sitting or standing position. Special forms of portraits are parade (pathetic pose, pompous covering with luxurious clothes and representative architecture in the background, often part of a powerful pillar), equestrian and  nude (there was a popular odalisque in the XIX century, presentation of a nude lavishing oriental woman). According to the number of persons, we can differentiate individual, double and group portrait. Self-portrait is a special field. According to format, there are miniature and medallion portraits, with a particular kind of painters miniaturists (present in India) and medallion sculptors.

nude (there was a popular odalisque in the XIX century, presentation of a nude lavishing oriental woman). According to the number of persons, we can differentiate individual, double and group portrait. Self-portrait is a special field. According to format, there are miniature and medallion portraits, with a particular kind of painters miniaturists (present in India) and medallion sculptors.

Such type of art did not exist in prehistoric times. Figures such as the Venus of Willendorf are without hints of the face, and its development began in the presentations of Assyrian monarchs and particularly in ancient Egypt. It was created there by extraordinary masters, mainly in plastics of stone hard to  process, such as porphyry and granite, and their exquisite skill was not only in the shades of fine psychological features, not even in realistic presentations, but in the fact that they were allowed to see the pharaoh only for a moment and from a distance. In Greek art, portrait had an incredible upswing, first as idealistic, reserved for divinities, and then realistic, developed in Hellenism. Ancient Romans ascended the realism of the presentation even more, considering their ancestor cult. On the borders of worlds, Egypt, Rome and Christianity, particularly realistic, so-called Fayum portraits of deceased were created, placed on mummies, made in encaustics, forerunners of icon painting, still looking fresh today. In early Middle Ages, the earthly form of human beings was not important and portrait art began dying away. Instead of a face, attributes – insignia and coats of arms – were often sufficient. It was cherished since the XIV century, first in the form of luminaries presented on altar wholes. That was

process, such as porphyry and granite, and their exquisite skill was not only in the shades of fine psychological features, not even in realistic presentations, but in the fact that they were allowed to see the pharaoh only for a moment and from a distance. In Greek art, portrait had an incredible upswing, first as idealistic, reserved for divinities, and then realistic, developed in Hellenism. Ancient Romans ascended the realism of the presentation even more, considering their ancestor cult. On the borders of worlds, Egypt, Rome and Christianity, particularly realistic, so-called Fayum portraits of deceased were created, placed on mummies, made in encaustics, forerunners of icon painting, still looking fresh today. In early Middle Ages, the earthly form of human beings was not important and portrait art began dying away. Instead of a face, attributes – insignia and coats of arms – were often sufficient. It was cherished since the XIV century, first in the form of luminaries presented on altar wholes. That was  when first self-portraits appeared in sculpture. The famous painting of Gothic master Jan van Eyck The Arnolfini Portrait is the first double portrait with full-length figures (double half-length portraits were known ever since ancient Rome). In renaissance, such form of creativeness experienced an amazing development, first from classical strict profile portraits. Further ascension took place in mannerism and baroque in continental Europe and England, with great masters after Leonardo da Vinci and Rafael, such as Rembrandt (he painted self-portraits during his entire creative career), Velasquez, Vermeer, Van Eyck, Halls, Rubens and others. Albrecht Dürer drew his first self-portrait at the age of thirteen, and then made several others in drawing and three in oil. One of them is the famous Self-Portrait in a Jerkin from 1500, in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the first real self-portrait as an autonomous individual painting, with a magnificent appearance, based on the image of Christ. Many consider that painting the best self-portrait in the history of art. An entirely separate form is imaginary portrait, not connected to a particular character, improved in Serbian art of the XX and XXI century, which the thematic exhibition in the Modern Gallery Valjevo is dedicated to.

when first self-portraits appeared in sculpture. The famous painting of Gothic master Jan van Eyck The Arnolfini Portrait is the first double portrait with full-length figures (double half-length portraits were known ever since ancient Rome). In renaissance, such form of creativeness experienced an amazing development, first from classical strict profile portraits. Further ascension took place in mannerism and baroque in continental Europe and England, with great masters after Leonardo da Vinci and Rafael, such as Rembrandt (he painted self-portraits during his entire creative career), Velasquez, Vermeer, Van Eyck, Halls, Rubens and others. Albrecht Dürer drew his first self-portrait at the age of thirteen, and then made several others in drawing and three in oil. One of them is the famous Self-Portrait in a Jerkin from 1500, in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the first real self-portrait as an autonomous individual painting, with a magnificent appearance, based on the image of Christ. Many consider that painting the best self-portrait in the history of art. An entirely separate form is imaginary portrait, not connected to a particular character, improved in Serbian art of the XX and XXI century, which the thematic exhibition in the Modern Gallery Valjevo is dedicated to.

LINE OF DEVELOPMENT IN SERBS

Portrait in Serbia has been developing since the Middle Ages. As the most important Serbian art historian Svetozar Radojčić first noticed and dedicated his work to that subject, Serbian older art is marked by interest in historical portrait, which makes it different from others from the Byzantine circle. Socrates, Plato, Aristoteles and Seneca are present on wall surfaces in the narthex of our Virgin of Ljeviš. Particularly frequent are magnificent presentations of the most important imaginary portrait – Jesus Christ, whom no painter has seen, although he is a historical person, so each artist has to start

Portrait in Serbia has been developing since the Middle Ages. As the most important Serbian art historian Svetozar Radojčić first noticed and dedicated his work to that subject, Serbian older art is marked by interest in historical portrait, which makes it different from others from the Byzantine circle. Socrates, Plato, Aristoteles and Seneca are present on wall surfaces in the narthex of our Virgin of Ljeviš. Particularly frequent are magnificent presentations of the most important imaginary portrait – Jesus Christ, whom no painter has seen, although he is a historical person, so each artist has to start  from his own vision and knowledge. Similar is with the Virgin and many holy people. Such art does not include profile since medieval masters considered profile as half a man. After the extinguishing of Serbo-Byzantine art in the transition period of Turkish occupation, portrait painting had an upswing with the appearance of a growingly richer civic society in Vojvodina in the XVIII and XIX centuries. Numerous presentations of such kind were created at the time. The probably most successful self-portrait was painted by Katarina Ivanović in 1836, at the very beginning of her painting career, at the

from his own vision and knowledge. Similar is with the Virgin and many holy people. Such art does not include profile since medieval masters considered profile as half a man. After the extinguishing of Serbo-Byzantine art in the transition period of Turkish occupation, portrait painting had an upswing with the appearance of a growingly richer civic society in Vojvodina in the XVIII and XIX centuries. Numerous presentations of such kind were created at the time. The probably most successful self-portrait was painted by Katarina Ivanović in 1836, at the very beginning of her painting career, at the  age of twenty-five. According to its sharpness, purity and self-awareness, it is unsurpassable. Standing above any categorization is the icon of Jesus Christ Pantocrator in Chilandar, from 1260–1277, created by a Serbian or Greek master, considered the most wonderful and most truthful portrait of the Savior in history.

age of twenty-five. According to its sharpness, purity and self-awareness, it is unsurpassable. Standing above any categorization is the icon of Jesus Christ Pantocrator in Chilandar, from 1260–1277, created by a Serbian or Greek master, considered the most wonderful and most truthful portrait of the Savior in history.

The nineteenth century is a time of penetration of photography and decline of portrait, although Ingres and Delacroix used it. Our greatest painters and sculptors were creating  portraits and self-portraits at the time. The first is the Self-Portrait of baroque master Stefan Tenecki, followed by the painting of Nikola Nešković from 1775 (National Museum, Belgrade). They were followed by numerous (self)portraits created by Dimitrije Avramović, Konstantin Danil, Đura Jakšić, Stevan Aleksić, Steva Todorović, Uroš Predić, Paja Jovanović, Đorđe Krstić, and sculptors Petar Ubavkić and Đorđe Jovanović. Female painters Mina Karadžić and Poleksija Todorović also painted portraits. This form of art was also accepted by the following generation of first Serbian modernists, from Nadežda Petrović, Kosta Miličević, Milan Milovanović and Branko Popović. Inevitable in the generation after were Sava Šumanović, Vasa Pomorišac, Ivan Tabaković, Nedeljko Gvozdenović, Milo Milunović, Milan Konjović, Ivan Radović, Kosta Hakman, Zora Petrović and, aside from our scene, Milena Pavlović-Barili.

portraits and self-portraits at the time. The first is the Self-Portrait of baroque master Stefan Tenecki, followed by the painting of Nikola Nešković from 1775 (National Museum, Belgrade). They were followed by numerous (self)portraits created by Dimitrije Avramović, Konstantin Danil, Đura Jakšić, Stevan Aleksić, Steva Todorović, Uroš Predić, Paja Jovanović, Đorđe Krstić, and sculptors Petar Ubavkić and Đorđe Jovanović. Female painters Mina Karadžić and Poleksija Todorović also painted portraits. This form of art was also accepted by the following generation of first Serbian modernists, from Nadežda Petrović, Kosta Miličević, Milan Milovanović and Branko Popović. Inevitable in the generation after were Sava Šumanović, Vasa Pomorišac, Ivan Tabaković, Nedeljko Gvozdenović, Milo Milunović, Milan Konjović, Ivan Radović, Kosta Hakman, Zora Petrović and, aside from our scene, Milena Pavlović-Barili.

PROBLEMS IN INTERPRETATION

Some of these artists continued creating after World War II, when the most important modern imaginary portrait was created, Petar Lubarda’s Gusle Player (based on several preparatory pictures), with which the artist passed on his interests to his students and followers. ”Mediala”, as a non-modernist group, further promoted imaginary portrait. High-quality portraits and self-portraits, except in museums and galleries, are also kept in private collections. One of the biggest and best is the collection of Nikola Bogdanović and his family in Sremska Mitrovica, including between 400 and 500 works. When speaking about Serbian high modernism, the

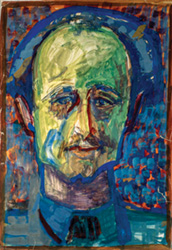

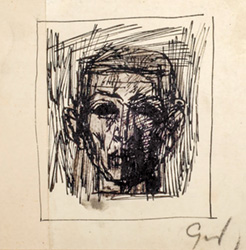

Some of these artists continued creating after World War II, when the most important modern imaginary portrait was created, Petar Lubarda’s Gusle Player (based on several preparatory pictures), with which the artist passed on his interests to his students and followers. ”Mediala”, as a non-modernist group, further promoted imaginary portrait. High-quality portraits and self-portraits, except in museums and galleries, are also kept in private collections. One of the biggest and best is the collection of Nikola Bogdanović and his family in Sremska Mitrovica, including between 400 and 500 works. When speaking about Serbian high modernism, the  period of the great flourishing of art between 1950 and 1980, when most museums and state galleries were opened, Bogdanović’ collection is the most important in Vojvodina after the gift-collection of Rajko Mamuzić. Nikola Bogdanović’ collection includes different types of works, from drawing, aquarelle and gouache, to oil on canvas. Some of them, such as the work of Mladen Srbinović, move from notes, self-portrait understood almost as a sketch, to ultimately serious oil Portrait, created by Jovanka Stojanović-Maksimović from 1953. Works of Majda

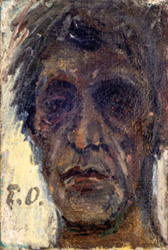

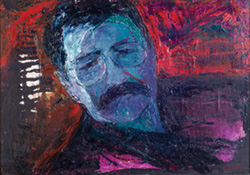

period of the great flourishing of art between 1950 and 1980, when most museums and state galleries were opened, Bogdanović’ collection is the most important in Vojvodina after the gift-collection of Rajko Mamuzić. Nikola Bogdanović’ collection includes different types of works, from drawing, aquarelle and gouache, to oil on canvas. Some of them, such as the work of Mladen Srbinović, move from notes, self-portrait understood almost as a sketch, to ultimately serious oil Portrait, created by Jovanka Stojanović-Maksimović from 1953. Works of Majda  Kurnik have a dark appearance, dramatically understood characters, and Petar Omčikus, in the excellent paintings from his early period (Banker Mesarović, 1953, Portrait of Nada, 1952) insists even more on realism, dark gamma and studiousness. Such is his Self-Portrait from 1972, created, like almost all his personal presentations, in dark shades, almost monochromatically, unlike portraits of other persons. The painter is the humblest and deepest when diving into his own personality. Similar case is with self-portrait of

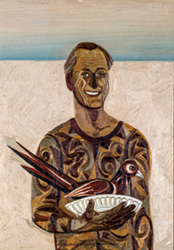

Kurnik have a dark appearance, dramatically understood characters, and Petar Omčikus, in the excellent paintings from his early period (Banker Mesarović, 1953, Portrait of Nada, 1952) insists even more on realism, dark gamma and studiousness. Such is his Self-Portrait from 1972, created, like almost all his personal presentations, in dark shades, almost monochromatically, unlike portraits of other persons. The painter is the humblest and deepest when diving into his own personality. Similar case is with self-portrait of  Miodrag Mića Popović from the same period. Portrait of a Girl, oil painted by Božidar Boža Ilić from the 1970s, represents a half-length figure in full color. Entirely different from these paintings is Stojan Ćelić’s drawing from the seventies, where he, in just a few lines, like a sketch, skillfully created the image of Shakespeare. A special place in the collection belongs to Olivera Kangrga, unjustly neglected important artist. Two self-portraits in pastel from 1952 and 1962 reveal her as an elegant, self-aware artist, whose works remind of Watteau and the best French pastelists. These self-portraits are one of the best in our recent art, showing that the

Miodrag Mića Popović from the same period. Portrait of a Girl, oil painted by Božidar Boža Ilić from the 1970s, represents a half-length figure in full color. Entirely different from these paintings is Stojan Ćelić’s drawing from the seventies, where he, in just a few lines, like a sketch, skillfully created the image of Shakespeare. A special place in the collection belongs to Olivera Kangrga, unjustly neglected important artist. Two self-portraits in pastel from 1952 and 1962 reveal her as an elegant, self-aware artist, whose works remind of Watteau and the best French pastelists. These self-portraits are one of the best in our recent art, showing that the  artist knows the forgotten secrets of representing incarnate. A separate group of paintings consist of oils of contemporary Russian masters, such as Alexei Parfenov, Sergei Mantzerev and great Russian painter Ivan Lubyenikov, which perfectly fit into Serbian modernism. Portrait and even more self-portrait are, besides landscape, forms of art which are not subject to iconographic interpretation, even when speaking about personifications. It is thus more difficult to develop conceptual knowledge, even less thematic or symbolic, therefore this text is also reduced to a more general review of Bogdanović’ collection.

artist knows the forgotten secrets of representing incarnate. A separate group of paintings consist of oils of contemporary Russian masters, such as Alexei Parfenov, Sergei Mantzerev and great Russian painter Ivan Lubyenikov, which perfectly fit into Serbian modernism. Portrait and even more self-portrait are, besides landscape, forms of art which are not subject to iconographic interpretation, even when speaking about personifications. It is thus more difficult to develop conceptual knowledge, even less thematic or symbolic, therefore this text is also reduced to a more general review of Bogdanović’ collection.